Every year, thousands of people end up in the hospital not because of an infection or accident, but because of something they took to feel better. A common painkiller. An antibiotic. A herbal supplement bought online. These aren’t rare mistakes - they’re silent, predictable dangers that most doctors and patients don’t see coming until it’s too late. This is drug-induced liver injury, or DILI. It doesn’t come with warning signs until the damage is already done. And it’s rising.

What Is Drug-Induced Liver Injury?

Your liver is your body’s main filter. It breaks down everything you swallow - medicines, supplements, even some foods. But sometimes, that process backfires. Instead of safely removing toxins, the liver turns them into harmful byproducts that attack its own cells. That’s DILI: liver damage caused by medications or supplements, not by viruses, alcohol, or genetics.

There are two main types. The first is intrinsic - predictable, dose-dependent, and unavoidable if you take too much. Acetaminophen (Tylenol) is the classic example. Taking more than 4 grams a day can cause serious liver damage. In the U.S., acetaminophen overdose is responsible for nearly half of all acute liver failure cases.

The second type is idiosyncratic - unpredictable, rare, and not tied to dose. You could take the same dose as someone else and be fine, while they end up in the ICU. This makes it harder to spot, and even harder to prevent. About 75% of all DILI cases fall into this category.

Top 5 High-Risk Medications

Not all drugs carry the same risk. Some are far more likely to hurt your liver than others. Here are the top offenders, backed by real-world data:

- Acetaminophen - The most common cause of acute liver failure in the U.S. A single dose over 7-10 grams can trigger toxicity. Even lower doses can be dangerous if you drink alcohol regularly, are malnourished, or have existing liver disease.

- Amoxicillin-clavulanate - This common antibiotic (brand name Augmentin) causes about 14% of all idiosyncratic DILI cases. It’s often prescribed for sinus infections or ear infections. Symptoms can show up weeks after you’ve finished the course - itching, yellow skin, dark urine.

- Isoniazid - Used to treat tuberculosis, this drug causes liver injury in about 1% of users. Risk jumps to 2-3% if you’re over 35. Many patients don’t realize their fatigue and nausea are signs of liver damage until their ALT levels spike above 1,000.

- Valproic acid - An antiseizure medication that can cause severe liver injury, especially in young children on multiple drugs. Fatality rates in severe cases reach 10-20%.

- Herbal and dietary supplements - Once considered safe, these are now linked to 20% of DILI cases in the U.S. Products with green tea extract, kava, anabolic steroids, and weight-loss blends are the worst offenders. Many people don’t even think of these as “medications,” so they don’t tell their doctors.

Statins, often blamed for liver damage, rarely cause serious harm. Only 1 in 50,000 users develop severe injury. But that doesn’t mean they’re harmless - mild enzyme elevations are common, and ignoring them can mask real problems.

How DILI Shows Up - Symptoms You Can’t Ignore

DILI doesn’t always scream for attention. Sometimes it whispers. That’s why so many people are misdiagnosed. Common symptoms include:

- Yellowing of the skin or eyes (jaundice)

- Dark urine

- Light-colored stools

- Unexplained fatigue

- Loss of appetite

- Nausea or vomiting

- Severe itching without a rash

- Pain in the upper right abdomen

One patient on Reddit described waiting three months before a doctor connected his itchy skin and tiredness to a cholesterol pill he’d been taking for a year. By then, his liver enzymes were through the roof.

Doctors use specific patterns to tell if the damage is to liver cells (hepatocellular) or bile ducts (cholestatic). High ALT (alanine aminotransferase) points to cell death - like with acetaminophen. High ALP (alkaline phosphatase) suggests bile flow is blocked - common with antibiotics like amoxicillin-clavulanate.

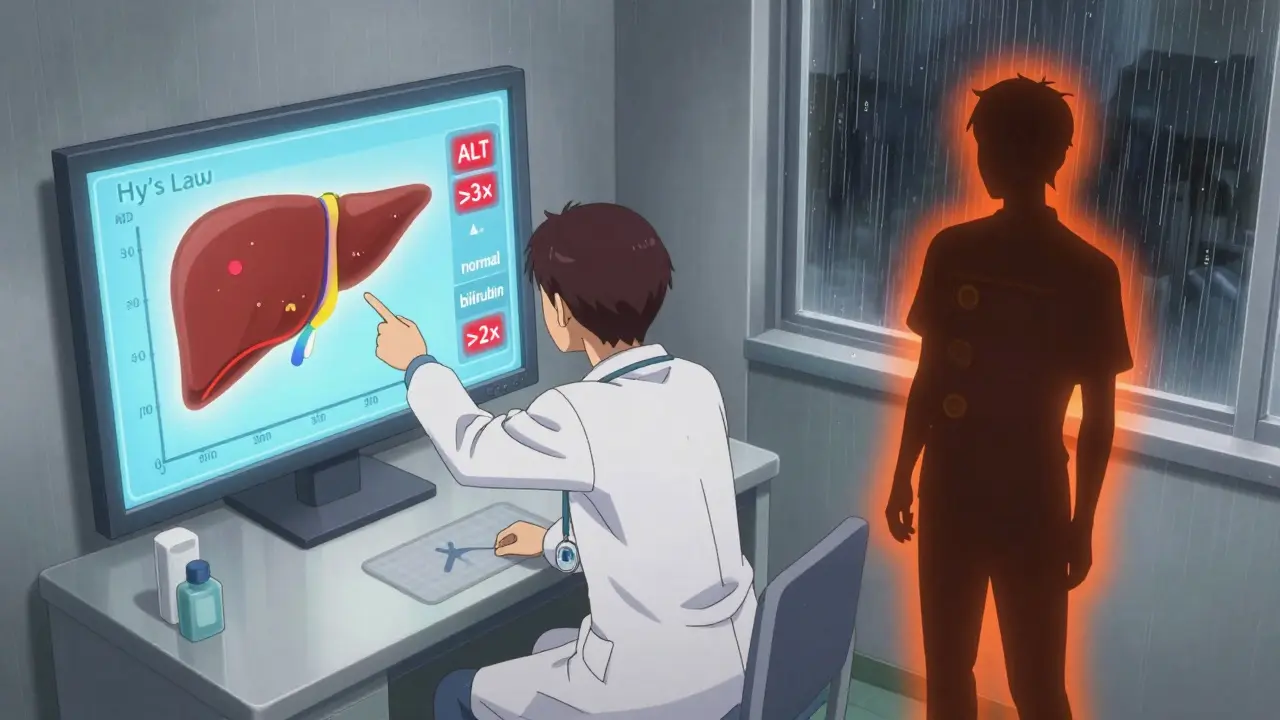

And here’s the scary part: if your ALT or AST is more than three times the normal level AND your bilirubin is more than double, you’re at risk for acute liver failure. This is called Hy’s Law - named after the doctor who discovered it in 1978. It’s still one of the most reliable predictors we have.

Who’s at Risk - And Why It’s Not Just About Dose

You might think, “I take my meds as directed, so I’m safe.” But that’s not always true. DILI doesn’t care about your compliance. It cares about your body.

- Age - People over 55 are more vulnerable. Liver metabolism slows down, and detox pathways get weaker.

- Gender - Women make up 63% of DILI cases. Hormonal differences may play a role.

- Genetics - Certain gene variants make you far more likely to react badly. HLA-B*57:01 increases risk of flucloxacillin injury by 80 times. HLA-DRB1*15:01 raises amoxicillin-clavulanate risk by 5.6 times. Genetic testing isn’t routine yet, but it’s coming.

- Multiple medications - Taking five or more drugs increases your risk dramatically. Interactions can create new toxins your liver wasn’t built to handle.

- Existing liver disease - Even mild fatty liver can make you more sensitive to drug damage.

And here’s something most people don’t know: herbal supplements aren’t regulated like drugs. A product labeled “natural” can contain hidden chemicals, heavy metals, or even prescription drugs. One study found that 25% of weight-loss supplements contained unlisted pharmaceuticals - including steroids and diuretics.

Monitoring Protocols That Actually Work

For some drugs, monitoring isn’t optional - it’s life-saving. Here’s what real guidelines recommend:

- Isoniazid (for TB) - Check liver enzymes before starting. Then monthly for the first three months. Stop immediately if ALT rises above 3-5 times normal or if you develop symptoms.

- Valproic acid - Baseline test, then every two weeks for the first six months, then every three months. Watch for confusion or vomiting - these can be early signs of hyperammonemia, not just liver damage.

- Acetaminophen - No routine monitoring needed for healthy adults taking ≤3 grams/day. But if you’re over 65, have liver disease, or drink alcohol, stick to ≤2 grams/day. Keep naloxone or N-acetylcysteine on hand if you’re at risk for overdose.

- Statins - Routine liver tests aren’t recommended. The cost outweighs the benefit. Instead, educate patients to report fatigue, nausea, or jaundice immediately.

- Herbal supplements - If you’re taking them, tell your doctor. Get a baseline liver test before starting, especially if you’re over 50 or have other liver risks.

Pharmacists are your best defense. A study showed that when pharmacists review all your medications - including supplements - they catch dangerous interactions before they happen. One case: a pharmacist spotted that a patient’s new antibiotic would clash with their seizure meds. She called the doctor. The patient never took the pills. No liver damage. No hospital stay.

What to Do If You Suspect DILI

If you’re on a high-risk drug and start feeling off, don’t wait. Don’t assume it’s “just a virus.”

- Stop the suspected medication immediately - but only after talking to your doctor. Some drugs can rebound dangerously if stopped cold.

- Get a liver panel: ALT, AST, ALP, bilirubin, and INR. Don’t rely on just one test.

- Ask about RUCAM scoring - a tool doctors use to rate how likely DILI is. A score of 8 or higher means it’s “highly probable.”

- Discontinue all supplements. Many patients don’t realize their “natural” tea or pill is the culprit.

- Follow up in 1-2 weeks. Liver enzymes often drop quickly once the drug is stopped. If they don’t, you may need a specialist.

Recovery usually takes 3-6 months. But 12% of cases lead to permanent damage. And in rare cases, a transplant is the only option. DILI accounts for about 13% of all liver transplants in the U.S.

What’s Changing - And What’s Coming

The science is catching up. In 2022, the FDA updated its guidance to require testing for mitochondrial toxicity in new drugs - a key mechanism behind past liver disasters like troglitazone. Researchers are now using AI to predict which chemical structures are likely to cause liver damage - with 82% accuracy.

Blood tests for new biomarkers like microRNA-122 and keratin-18 are in trials. These can show liver damage 12-24 hours before ALT rises. That’s huge. It could mean catching injury before it’s visible on a blood test.

Hospitals are also starting to use electronic alerts. If your chart shows you’re on isoniazid and amoxicillin-clavulanate at the same time, your doctor gets a warning. Early data shows this could prevent 15-20% of severe DILI cases.

But the biggest change? Awareness. More doctors are asking about supplements. More patients are speaking up. And more pharmacists are stepping in as frontline defenders.

Final Takeaway: Knowledge Is Your Shield

You can’t avoid every risk. But you can reduce it. If you’re taking any medication long-term - especially antibiotics, antiseizure drugs, TB meds, or supplements - ask your doctor: “Could this hurt my liver?”

Get a baseline liver test. Keep track of your symptoms. Don’t ignore fatigue or itching. Tell your pharmacist everything you take - even the “natural” stuff. And if something feels wrong, don’t wait for it to get worse. Your liver doesn’t have a pain center. It won’t scream until it’s too late.

Drug-induced liver injury isn’t rare. It’s silent. And it’s preventable - if you know what to look for.

Can over-the-counter painkillers like ibuprofen cause liver damage?

Ibuprofen and other NSAIDs rarely cause serious liver injury. They’re more likely to affect the kidneys or stomach. But if you take high doses for a long time, especially with alcohol or other liver stressors, mild enzyme elevations can happen. Severe DILI from NSAIDs is very uncommon - less than 1 in 100,000 users.

Is it safe to take herbal supplements if I have a healthy liver?

Not necessarily. Many herbal products contain hidden ingredients, heavy metals, or compounds that overload the liver’s detox system. Green tea extract, kava, and weight-loss blends have all been linked to serious liver injury - even in people with no prior liver problems. Always check with your doctor before starting any supplement.

How long does it take for the liver to recover from DILI?

Most people see improvement in liver enzymes within 1-2 weeks after stopping the drug. Full recovery usually takes 3-6 months. But in about 12% of cases, there’s permanent damage. Recovery depends on how severe the injury was, how quickly the drug was stopped, and whether complications like jaundice or high bilirubin occurred.

Can DILI happen after I stop taking a drug?

Yes. Idiosyncratic DILI often appears 1-12 weeks after starting a drug - but sometimes symptoms show up weeks after you’ve stopped taking it. That’s why it’s so easy to miss. If you develop jaundice or fatigue after finishing a course of antibiotics or a new supplement, don’t assume it’s unrelated.

Are blood tests enough to detect DILI early?

Blood tests like ALT and AST are the main tools, but they’re not perfect. Some people have severe liver damage with only mild enzyme rises. Others have high enzymes but no symptoms. That’s why symptoms matter too - itching, dark urine, fatigue. The best approach is combining blood tests with clinical signs. New biomarkers like microRNA-122 are being tested to catch injury even earlier.

Should I avoid all medications that carry DILI risk?

No. Many of these drugs are essential - like antibiotics for serious infections or isoniazid for tuberculosis. The goal isn’t to avoid them, but to use them safely. That means monitoring, knowing the signs, and never taking supplements without telling your doctor. The risk is low for most people - but the consequences are high if you ignore the warning signs.

OMG I KNEW IT. My cousin took Augmentin for a sinus infection and woke up yellow. Like, full-on jaundice. Docs said it was "viral" for 3 weeks. She almost died. This is why I dont trust American medicine anymore. #DILIisreal