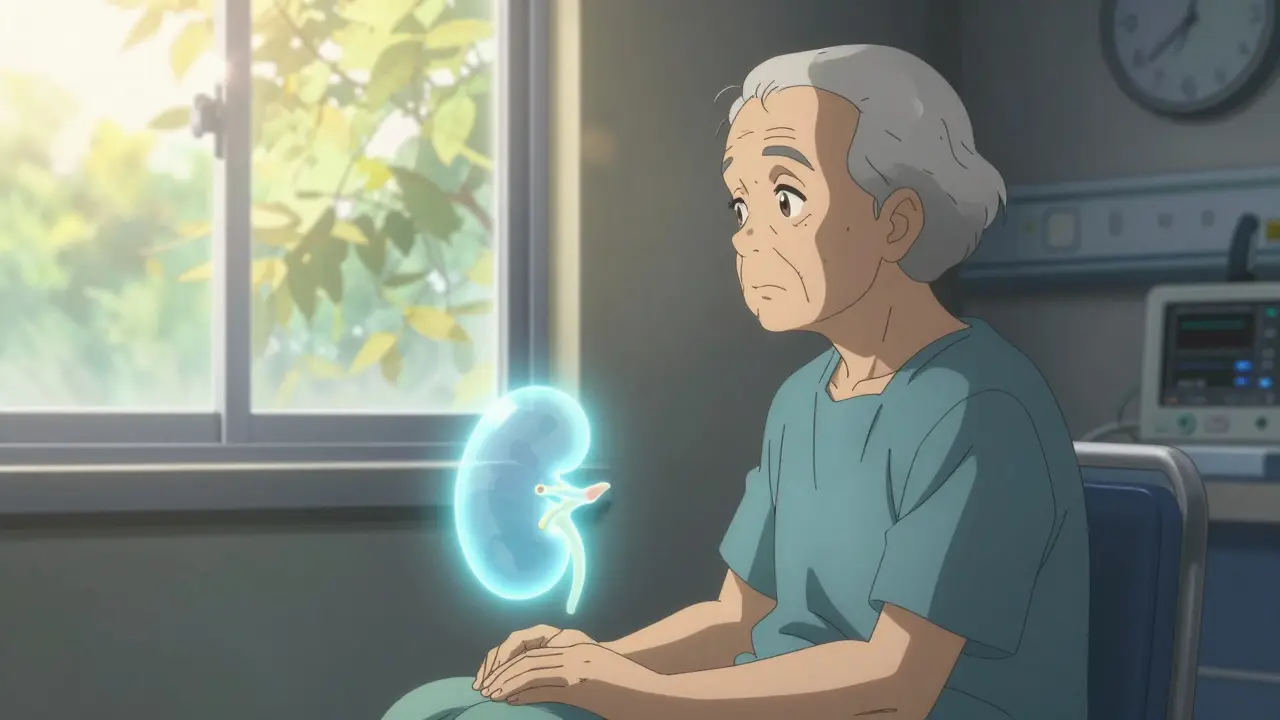

When your kidneys fail, life changes. Dialysis keeps you alive, but it doesn’t give you back your life. A kidney transplant can. It’s not a cure, but for most people with end-stage renal disease (ESRD), it’s the best shot at returning to normal activities-working, traveling, spending time with family-without being tied to a machine three times a week.

Who Can Get a Kidney Transplant?

Not everyone with kidney failure qualifies. The goal isn’t just to replace a failing organ-it’s to give you the best chance at long-term survival and quality of life. That means transplant centers screen carefully. The main requirement is end-stage renal disease, meaning your kidneys are working at 15% or less of normal capacity. This is measured by your glomerular filtration rate (GFR). Most centers require a GFR of 20 mL/min or lower. Some, like Mayo Clinic, may consider patients with a GFR up to 25 mL/min if their kidney function is dropping fast or if they have a living donor ready. Age isn’t a hard barrier. While Vanderbilt University Medical Center flags age 75+ as a relative contraindication, UCLA doesn’t set an upper limit. Instead, they look at your overall health. A healthy 80-year-old with strong heart function and no other major illnesses has a better chance than a 60-year-old with uncontrolled diabetes and heart disease. Body weight matters too. Obesity increases surgical risks and reduces transplant success. Mayo Clinic won’t list anyone with a BMI over 45. Vanderbilt considers a BMI of 35-44 a red flag and over 45 an automatic disqualifier. Why? Studies show obese patients have a 35% higher risk of surgical complications and a 20% higher chance of graft failure. Many centers require weight loss before listing. Your heart and lungs need to be strong enough to handle major surgery. If you have severe pulmonary hypertension-where pressure in the lung arteries hits 50 mm Hg or higher-you’re likely not a candidate. Vanderbilt sets the bar even higher, rejecting anyone with pressures above 70 mm Hg. If you’re on long-term oxygen because of COPD or other lung disease, most centers will say no. Your heart’s pumping strength, measured by ejection fraction, usually needs to be above 35-40%.What Disqualifies You?

Some conditions are absolute barriers. You can’t get a transplant if you have:- Active cancer that hasn’t been treated or is likely to return. Most centers require at least 2-5 years of remission, depending on the cancer type.

- Untreated, ongoing infections like tuberculosis or hepatitis B with active viral replication.

- Uncontrolled substance abuse-alcohol, opioids, methamphetamine. Recovery and sobriety for at least six months are typically required.

- Severe, untreated mental illness that would make it impossible to take daily medications.

- HIV with a CD4 count under 200 or a detectable viral load. (Note: HIV-positive patients can now receive transplants in many centers, but only if their virus is well-controlled.)

The Evaluation Process

Getting listed isn’t just a blood test and a quick chat. It’s a months-long process that looks at every part of your life. You’ll go through:- Full blood work, including tissue typing to match you with a donor

- Cancer screenings-colonoscopy, mammogram, skin checks

- Chest X-ray and EKG

- Tests for hepatitis, HIV, and other viruses

- Heart tests like echocardiograms or stress tests, especially if you’re over 50

- Pulmonary function tests if you have breathing issues

What Happens During Surgery?

The surgery itself takes 3 to 4 hours. You’re under general anesthesia. The surgeon places the new kidney in your lower abdomen, connects its blood vessels to your iliac artery and vein, and attaches the ureter to your bladder. Your own kidneys are usually left in place unless they’re causing pain, infection, or high blood pressure. The new kidney often starts working right away. In fact, many patients pee within hours. But don’t be surprised if it doesn’t. About 20% of kidneys from deceased donors take a few days to start producing urine fully. This is called delayed graft function. You might need dialysis for a week or two while it wakes up. It’s not a sign of failure-it’s a common delay. Living donor transplants tend to work faster and last longer. Why? The kidney comes from a healthy person, is transplanted immediately after removal, and doesn’t sit in cold storage. The kidney’s “cold ischemia time” is zero.Life After Transplant: The Real Challenge

The surgery is just the beginning. The real work starts after you wake up. You’ll take immunosuppressants for the rest of your life. These drugs stop your immune system from attacking the new kidney. Common regimens include:- Tacrolimus or cyclosporine (calcineurin inhibitors)

- Mycophenolate mofetil or azathioprine (antiproliferatives)

- Prednisone (a steroid, often tapered over time)

What’s New in Kidney Transplantation?

The field is evolving fast. One big advance is the Kidney Donor Profile Index (KDPI). This score, used since 2014, helps match kidneys with the longest expected life to the patients who need them most. A low KDPI (under 20%) means a kidney from a young, healthy donor. A high KDPI (over 85%) means an older donor or one with health issues like high blood pressure. You might think: “Why take a kidney with a high KDPI?” But studies show even these kidneys give patients a much better chance than staying on dialysis. A 60-year-old with a high-KDPI kidney lives longer and feels better than if they waited for a perfect match. Living donation is growing. More people are choosing to donate a kidney to a friend, family member, or even a stranger through paired exchange programs. The National Kidney Registry reports 97% one-year survival for living donor transplants-better than any other type. Research is now focused on tolerance. Can we teach the immune system to accept the new kidney without lifelong drugs? Early trials at Stanford and the University of Minnesota are showing promise. Some patients have successfully reduced or stopped immunosuppressants after years of stable function. This could change everything.What to Expect in the Long Run

You’ll need to be your own best advocate. Take your pills every day, even when you feel great. Skip the grapefruit-it interferes with tacrolimus. Watch your salt and protein intake. Stay active. Get vaccinated. Avoid people who are sick. You’ll have good days and bad days. Maybe you’ll have a flare-up of high blood pressure. Maybe you’ll get a urinary tract infection. Maybe you’ll worry the kidney is failing. These are normal fears. But with regular monitoring, most problems are caught early and treated. The goal isn’t perfection. It’s more time. More energy. More moments with your grandkids. More walks in the park. More mornings without exhaustion. A kidney transplant doesn’t erase kidney disease. But it gives you back your life.Can you get a kidney transplant without being on dialysis?

Yes. Many patients are listed before starting dialysis, especially if they have a living donor. Transplant centers often consider patients with a GFR below 20 mL/min-even if they haven’t started dialysis yet. Being off dialysis before transplant improves recovery and long-term outcomes.

How long is the wait for a kidney transplant?

It varies widely. In the U.S., the average wait is 3-5 years for a deceased donor kidney. But with a living donor, you can go from evaluation to surgery in as little as 2-6 months. Waiting times are shorter in countries with active living donation programs. Your location, blood type, and tissue match also affect wait time.

Can you donate a kidney if you’re over 60?

Yes. There’s no upper age limit for living kidney donation. Donors over 60 are evaluated carefully for overall health, kidney function, and risk of future disease. Many healthy older adults make excellent donors and have no long-term health issues after donation.

What happens if the transplanted kidney fails?

If the transplant fails, you return to dialysis. You can be relisted for another transplant if you’re still a good candidate. Many people receive more than one transplant over their lifetime. The key is staying healthy between transplants-managing blood pressure, avoiding infections, and following medical advice.

Are there alternatives to lifelong immunosuppressants?

Not yet for most patients. But clinical trials are testing tolerance-inducing therapies that could allow some recipients to stop immunosuppressants safely. These are still experimental and only available in research settings. For now, lifelong medication is the standard.

so u know the gov is secretly using transplant data to track who's 'worthy' of organs? they flag people who use too much salt or don't yoga enough. my cousin got denied because she liked pizza. they said her 'lifestyle noncompliance score' was too high. it's all a scam. they're just rationing based on who they think deserves to live.

and don't get me started on the kidney registry. it's all coded. i've seen the spreadsheets. they prioritize the rich. the poor? they get dialysis until they die quietly.