When a brand-name drug’s patent runs out, the promise of lower prices kicks in-thanks to generic versions. But what if the same company that made the brand-name drug launches its own generic version? That’s an authorized generic, and it’s reshaping how competition works in the pharmaceutical market. Far from helping consumers, it often blocks real generic competitors from gaining the market share they’re legally entitled to.

What Is an Authorized Generic?

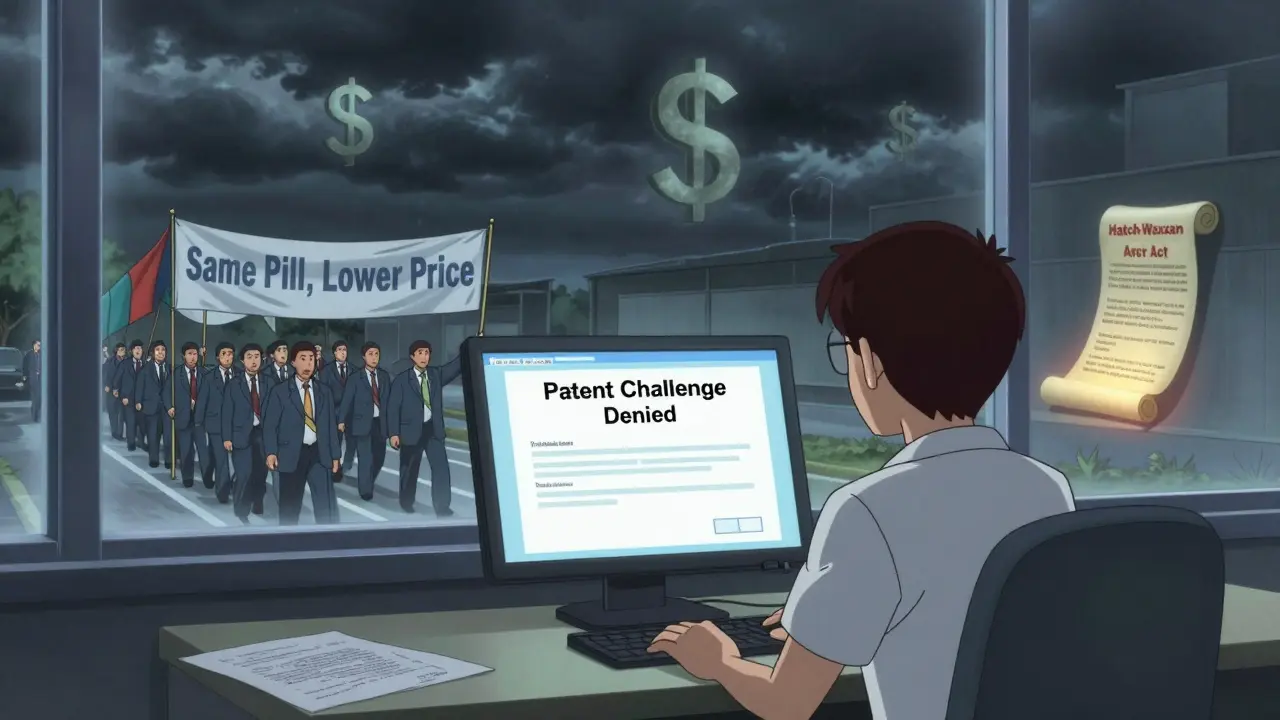

An authorized generic is a drug that’s chemically identical to a brand-name medication, but sold under a generic label. It’s made by the original brand company-or licensed to a partner-and enters the market at the same time as the first independent generic. No new clinical trials are needed. It’s the same pill, same factory, same packaging-just a different name and a lower sticker price. This isn’t a loophole. It’s legal under the Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984, which was designed to speed up generic access. The law gives the first generic company that challenges a patent a 180-day window to be the only generic on the market. That’s supposed to be their reward for taking the legal risk. But authorized generics turn that reward into a race they can’t win.How Authorized Generics Undermine the 180-Day Exclusivity

The 180-day exclusivity period is meant to be a financial lifeline for independent generic manufacturers. During that time, they’re the only generic sellers. That lets them capture 80-90% of the generic market and recoup the millions spent on patent litigation. But when an authorized generic shows up-often within 30 days of the first generic’s launch-it steals that advantage. The FTC found that when an authorized generic enters, it grabs 25-35% of the market share right away. That means the first generic doesn’t get to be the sole low-price option. Instead, they’re stuck competing against a version of the brand drug that’s priced higher than true generics but lower than the original brand. The result? First-filer generic companies see their revenues drop by 40-52% during the exclusivity period. And the damage lasts. Three years later, those same companies are still earning 53-62% less than they would have without an authorized generic.The Settlement Trap: Paying to Delay Competition

Here’s where it gets darker. Between 2004 and 2010, about 25% of patent settlements between brand and generic companies included secret deals: the brand company agreed not to launch an authorized generic-in exchange for the generic delaying its market entry. These deals, called “reverse payments,” are anti-competitive. The brand pays the generic not to compete. And by promising not to launch an authorized generic, the brand removes the biggest threat to the generic’s profitability. In return, the generic delays entry by an average of 37.9 months. That’s over three years of monopoly pricing on drugs worth billions. The FTC called these arrangements the “most egregious form of anti-competitive behavior” in pharma. Courts have since ruled such payments can violate antitrust laws, but the practice didn’t vanish. Even today, legal agreements around authorized generics are a standard part of patent litigation settlements.

Who Benefits? Who Gets Hurt?

Branded drug companies say authorized generics help consumers by lowering prices faster. They point to a 2022 Health Affairs study showing pharmacies paid 13-18% less when an authorized generic was available. But that’s misleading. The savings come from splitting the market-not from real competition. Real generic manufacturers, like Teva, lost $275 million in revenue on specific products because of authorized generics. Independent companies can’t compete with a version of the same drug sold by the company that just sued them in court. It’s like a restaurant owner opening a second location with the same menu, same chef, same food-but calling it “cheap version,” right next door to the original. Pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs), who negotiate drug prices for insurers, often support authorized generics. A 2023 survey found 68% prefer formularies that include them. Why? Because they get another low-price option to push on insurers. But that doesn’t help the system long-term. It just delays the real discount that comes when multiple independent generics flood the market.The Decline-and the Fight Back

The use of authorized generics has dropped. In 2010, they appeared in 42% of markets with first-filer exclusivity. By 2022, that fell to 28%. Why? Pressure from regulators. The FTC has opened 17 investigations since 2020 into agreements that delay authorized generic entry. In 2022, they made it clear: “We will challenge any arrangement that uses authorized generics to circumvent the competitive structure Congress established in Hatch-Waxman.” Congress has tried to fix this too. The Preserve Access to Affordable Generics and Biosimilars Act, reintroduced in 2023, would ban any deal that blocks an authorized generic from entering the market. It’s not law yet-but it’s gaining support from both Democrats and Republicans.

What This Means for Patients

Patients don’t see the backroom deals. They just notice that when a drug goes generic, the price doesn’t drop as much-or as fast-as expected. That’s because authorized generics create a pricing floor. Instead of a steep drop to 80-90% below brand price, patients get a moderate drop to 50-60% below, then a slow, uneven fall. For drugs with low sales-under $27 million a year-authorized generics make it less likely any generic company will even try to challenge the patent. Why risk millions in legal fees if you know the brand will just launch its own version and steal your profits? That means fewer generic challenges. Fewer competitors. Slower price drops. And patients pay more for longer.The Bigger Picture: A Broken System

The Hatch-Waxman Act was meant to balance innovation and access. It gave brand companies patent protection, but also created a fast track for generics. Authorized generics break that balance. They turn the incentive system upside down. Instead of rewarding the first generic company for taking on the legal risk, the system now rewards the brand company for outmaneuvering them. The result? A market where competition is controlled, not free. The data is clear: authorized generics reduce the financial reward for challenging patents. That leads to fewer challenges. Fewer challenges mean fewer generics. Fewer generics mean higher prices for years. This isn’t about big pharma being evil. It’s about a system that lets them play by rules that weren’t written for them. And until Congress closes that gap, patients will keep paying the price.Are authorized generics the same as regular generics?

Yes, chemically and physically. Authorized generics are made by the brand-name company using the same formula, same ingredients, same factory. The only difference is the label and the price. Regular generics are made by independent companies that had to prove bioequivalence to the brand drug. Authorized generics skip that step because they’re identical from the start.

Why do brand companies launch authorized generics?

To protect their profits. When a patent expires, the brand company loses its monopoly. But if they launch their own generic, they can keep a big slice of the market. They avoid losing everything to a single independent generic. It’s a way to soften the financial blow while still controlling pricing.

Do authorized generics lower drug prices for consumers?

They lower prices a little-but not as much as real competition. An authorized generic might be 15-20% cheaper than the brand, but still 25-30% more expensive than a true generic. That means patients pay more than they should. Real price drops happen only when multiple independent generics enter the market-and authorized generics often prevent that from happening.

Is it legal for brand companies to launch authorized generics?

Yes, it’s currently legal under FDA rules. The Hatch-Waxman Act doesn’t ban it. But if a brand company agrees not to launch one in exchange for a generic delaying entry, that’s illegal under antitrust law. The FTC has been cracking down on those kinds of deals since 2013.

What’s being done to stop authorized generics from hurting competition?

The FTC is actively investigating deals that use authorized generics to delay competition. Congress is also trying to pass laws like the Preserve Access to Affordable Generics and Biosimilars Act, which would ban agreements that block authorized generics. Some courts have ruled reverse payments illegal. But until laws change, the practice continues, though it’s becoming less common.

How do authorized generics affect new generic companies trying to enter the market?

They make it harder. If a generic company knows a brand will launch its own version, they’re less likely to spend millions on a patent lawsuit. For drugs with low sales, the risk isn’t worth it. That means fewer challengers overall-and fewer generics on the market long-term. That’s exactly what the brand companies want.

Authorized generics? More like authorized monopolies. The Hatch-Waxman Act was supposed to be a lifeline for generics, not a corporate playpen for Big Pharma to stitch their own patent netting. You think you're getting competition? Nah. You're getting a velvet-gloved chokehold disguised as a discount. The FTC's been screaming into the wind for a decade, and still, these deals slide through like grease on a patent lawyer's palm. This isn't innovation. It's financial cannibalism wrapped in a white coat.