When you hear the word radiation, you might think of nuclear accidents or X-ray machines at the dentist. But for millions of people with cancer, radiation is a precise, life-saving tool. Radiation therapy doesn’t just zap tumors-it shatters their DNA, stopping them from multiplying and forcing them to die. It’s not magic. It’s biology. And understanding how it works makes all the difference.

How Radiation Breaks DNA

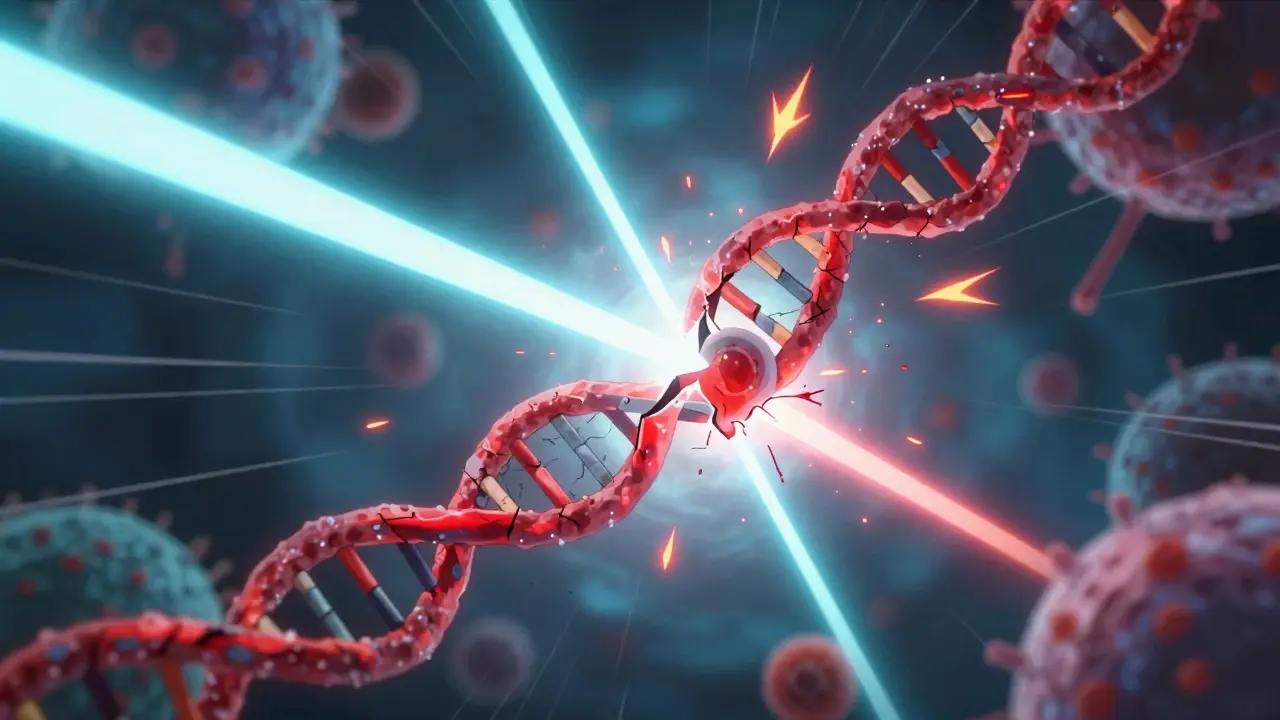

Radiation therapy uses high-energy particles or waves-usually X-rays or protons-to target cancer cells. The real damage happens inside the cell’s nucleus, where DNA lives. Ionizing radiation strips electrons from atoms, creating charged particles called ions. This process, called ionization, directly breaks the chemical bonds holding DNA strands together. The most dangerous kind of break? A double-strand break. When both strands of the DNA helix snap at the same spot, the cell can’t easily fix it. But radiation doesn’t always hit DNA directly. More often, it hits water molecules inside the cell. That creates reactive oxygen species-tiny, unstable molecules that go on a destructive spree. They chew through proteins, puncture cell membranes, and, most importantly, attack DNA. This indirect damage is actually responsible for about two-thirds of radiation’s killing power. Think of it like a bomb going off in a room: some debris flies straight at targets, but most damage comes from flying glass and shattered furniture.What Happens When DNA Is Broken?

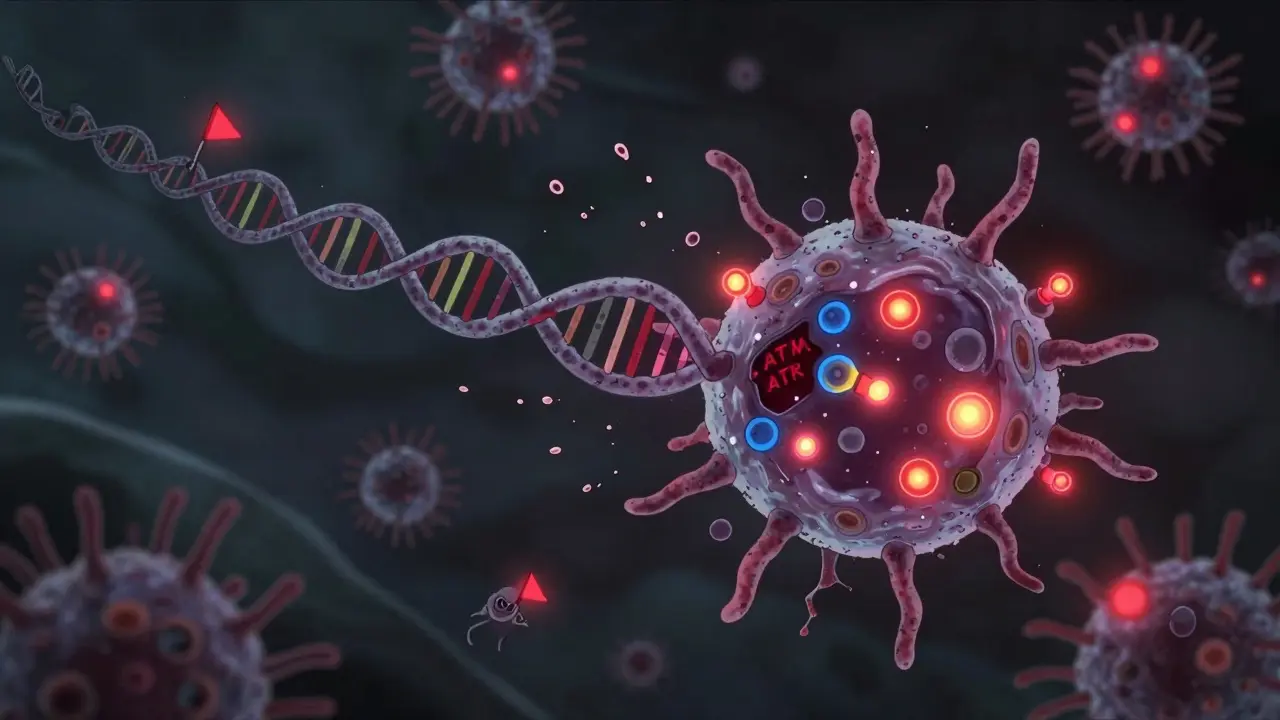

Cells aren’t helpless. They have emergency systems to detect and repair DNA damage. Two key proteins, ATM and ATR, act like alarms. When they sense a double-strand break, they trigger a cascade of signals that pause the cell cycle. The cell stops dividing and tries to fix the damage. There are two main repair crews: non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) and homologous recombination (HR). NHEJ is fast but sloppy. It glues broken ends back together, even if it messes up the sequence. That’s often enough to kill the cell. HR is more accurate-it uses a healthy copy of DNA as a template to rebuild the break. But here’s the twist: cancer cells that rely on HR often die quietly. They fix the damage, survive, and keep dividing. That’s not what doctors want. New research from the CMRI in Australia found something shocking. Cancer cells that can’t use HR-like those with BRCA2 mutations-don’t die quietly. Instead, they leak signals that scream "I’m damaged!" to the immune system. These cells trigger an inflammatory response, turning the tumor into a beacon for immune cells. That’s a game-changer. It means radiation isn’t just killing cancer cells on its own-it can wake up the body’s own defenses.

The Three Ways Radiation Kills Cancer Cells

There’s no single way radiation ends a cancer cell’s life. It’s a triple threat:- Apoptosis: Programmed cell death. The cell activates its own suicide switch, shrinking and breaking apart cleanly. This happens mostly in sensitive cells like those in the gut lining or bone marrow.

- Reproductive failure: The cell survives the initial damage but can’t divide again. It might look fine, but it’s sterile. This is how most solid tumors are stopped. Even if a cell doesn’t die right away, if it can’t multiply, the tumor shrinks over time.

- Mitotic catastrophe: The cell tries to divide with broken DNA. The result? A messy, failed division. Chromosomes fly everywhere. The cell either dies on the spot or becomes so unstable it dies later.

There’s also a third pathway, less talked about but just as important: the ceramide pathway. Radiation activates an enzyme that turns sphingomyelin into ceramide-a signaling molecule that triggers apoptosis from within the cell membrane. This pathway is especially strong in blood vessels feeding tumors. High-dose radiation, like in SBRT, can collapse these vessels, starving the tumor days after treatment.

Why Some Tumors Resist Radiation

Not all cancers respond the same. About 30-40% of tumors become resistant. Why? One big reason? Better DNA repair. Some cancer cells crank up their repair machinery. They produce more ATM, more NHEJ proteins, more HR tools. It’s like upgrading from a flashlight to a full repair crew. Another reason? Low oxygen. Radiation needs oxygen to create those destructive reactive oxygen species. Tumors often have dark, oxygen-starved zones. Cells there can need up to three times more radiation to die. There’s also the tumor microenvironment. Surrounding fibroblasts and immune cells can shield cancer cells, releasing chemicals that help them survive. And some tumors have mutations that turn off the p53 gene-the "guardian of the genome." Without p53, cells don’t pause to repair DNA or trigger apoptosis. They just keep dividing, even with broken DNA. A 2021 study on head and neck cancer showed patients with low levels of 53BP1-a protein involved in DNA repair-had better outcomes. Their tumors responded better to radiation. That’s not random. It means the repair system itself can be a predictor of success.

The Future: Radiation Meets Immunotherapy

The biggest breakthroughs aren’t coming from bigger doses or faster machines. They’re coming from combining radiation with other treatments. The CMRI findings about HR-deficient cells releasing immune signals have opened the door to a new era. If you block HR-say, with a drug like olaparib, a PARP inhibitor-you force cancer cells to die in a way that wakes up the immune system. That’s why clinical trials are now pairing radiation with immunotherapy drugs like pembrolizumab. One trial in metastatic lung cancer showed the response rate jumped from 22% to 36% when radiation was added to immunotherapy. That’s not a small bump. It’s a doubling of hope. Even more exciting? FLASH radiotherapy. It delivers the full radiation dose in less than a second-over 40 grays per second. In animal studies, it kills tumors just as well but spares healthy tissue far better. Human trials started in 2020. If it works at scale, it could mean fewer side effects and higher doses for stubborn tumors.What This Means for Patients

If you’re facing radiation therapy, know this: it’s not just about burning cancer. It’s about breaking its code. The goal isn’t just to kill cells-it’s to make sure they die in a way that helps your body finish the job. Your treatment plan isn’t one-size-fits-all. If you have a BRCA mutation, your tumor might respond better to radiation combined with a PARP inhibitor. If your tumor is in a low-oxygen area, your team might use oxygen-enhancing techniques or switch to proton therapy. If your cancer is stubborn, they might combine radiation with immunotherapy. Radiation therapy isn’t perfect. But it’s getting smarter. It’s no longer just a blunt tool. It’s becoming a targeted, intelligent system-working with your body, not just against it.Does radiation therapy hurt during treatment?

No, you won’t feel anything during the actual radiation delivery. It’s like getting an X-ray-you lie still, the machine moves around you, and you don’t feel heat, pain, or tingling. The side effects come later, from damage to nearby healthy tissue, not from the radiation itself during treatment.

How many sessions of radiation therapy are typical?

It depends on the cancer type and goal. For curative treatment, most patients get 20-40 sessions over 4-8 weeks. For stereotactic treatments (like SBRT), you might only need 1-5 sessions. Each session lasts about 15-30 minutes, but the actual radiation time is just a few minutes.

Can radiation therapy cure cancer on its own?

Yes, for many early-stage cancers-like prostate, cervical, or early lung cancer-radiation alone can be curative. For others, it’s used with surgery or chemotherapy to shrink tumors before removal or kill leftover cells after. The goal isn’t always cure; sometimes it’s control, pain relief, or preventing spread.

Why does radiation cause fatigue?

Fatigue comes from your body working hard to repair damaged healthy cells and fight inflammation. Radiation doesn’t just hit cancer-it affects normal tissue too. Your immune system is busy, your energy reserves are drained, and your body is in repair mode. Fatigue often builds up over the course of treatment and can last weeks after it ends.

Is radiation therapy safe for older patients?

Yes. Age alone doesn’t make radiation unsafe. Many older adults tolerate it well, especially with modern techniques that spare healthy tissue. Doctors consider overall health, organ function, and life expectancy-not just age-when planning treatment. In fact, for some older patients with early cancer, radiation is safer than surgery.

Radiation-induced double-strand breaks are the real killers here. NHEJ is a mess-ligase just slaps ends together like duct tape on a ruptured pipe. But HR-deficient cells? They’re screaming into the void with cytosolic DNA fragments activating cGAS-STING. That’s not just cell death-that’s immunogenic cell death. We’re talking about turning tumors into in situ vaccines. The CMRI paper was a bombshell. PARPi + RT isn’t just synergistic-it’s a paradigm shift. Stop thinking of radiation as a scalpel. Think of it as a molecular trigger for systemic immunity.