High-Altitude Sedative Safety Checker

Check if your sleep aid or medication is safe at high altitude. Based on CDC, Wilderness Medical Society, and clinical studies.

Your Altitude

Your Substance

When you’re heading up into the mountains-whether for hiking, skiing, or climbing-you might think a little help sleeping is harmless. After all, you’re tired, the air is thin, and the nights are long. But what if that sleeping pill or glass of wine could actually be putting your oxygen levels in danger? At elevations above 2,500 meters (8,200 feet), your body is already working harder just to breathe. Add sedatives into the mix, and you’re setting up a dangerous chain reaction that can drop your blood oxygen to life-threatening levels.

Why Your Body Struggles at High Altitude

At 3,000 meters, the air has about 30% less oxygen than at sea level. That doesn’t mean you feel dizzy right away. Instead, your body tries to adapt by breathing faster and deeper. This is called the hypoxic ventilatory response. It’s your body’s natural way of pulling in more oxygen. But here’s the catch: as you breathe faster, you blow off too much carbon dioxide. That makes your blood more alkaline, which then tells your brain to slow down your breathing. The result? A cycle of rapid breathing followed by pauses-called periodic breathing-that affects up to 75% of travelers at this elevation.

This isn’t just annoying-it’s a red flag. When your breathing slows, your oxygen levels drop. And if something else is already slowing your breathing? You’re in trouble.

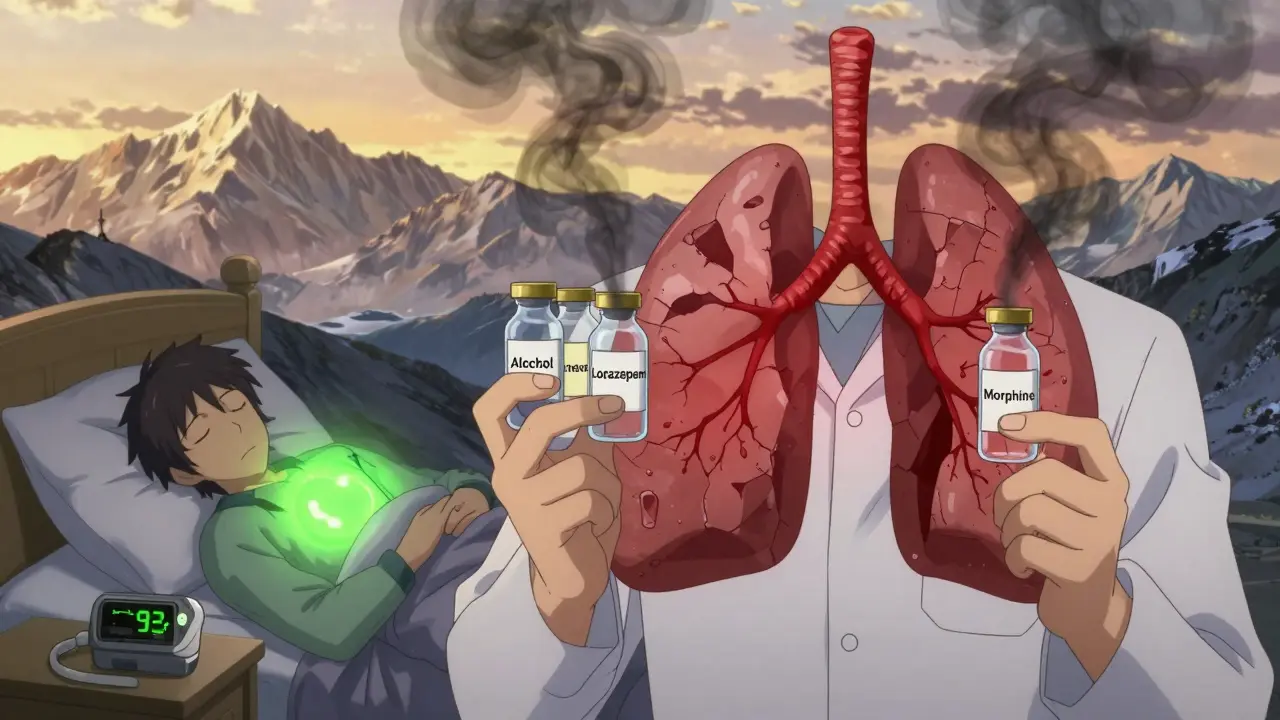

How Sedatives Make Things Worse

Sedatives-whether they’re prescription, over-the-counter, or alcohol-work by calming the central nervous system. That includes the part of your brain that controls breathing. At high altitude, where your body is already struggling to keep oxygen levels stable, any extra suppression can be deadly.

Alcohol, for example, reduces your hypoxic ventilatory response by about 25% even at low doses (0.05% blood alcohol). That means if you have a beer after arriving at 3,500 meters, your body loses a quarter of its natural ability to respond to low oxygen. Studies show this can drop your nighttime oxygen saturation by 5-10 percentage points. One traveler in Nepal reported SpO2 levels plunging from 88% to 76% after taking lorazepam-a benzodiazepine-at 4,200 meters. That’s a drop from moderate hypoxia into critical danger.

Benzodiazepines like diazepam and lorazepam cut ventilation by 15-30% at altitude, according to controlled studies. Opioids are even worse. A 2010 case series found that therapeutic doses of morphine at 4,500 meters caused oxygen saturation to fall below 80%-a level where organ damage can begin. And these aren’t rare cases. The CDC, Cleveland Clinic, Healthdirect Australia, and the Wilderness Medical Society all agree: avoid sedatives at high altitude.

Not All Sleep Aids Are Created Equal

It’s not all doom and gloom. Some sleep aids carry far less risk. The key is whether they interfere with your body’s natural breathing response.

Short-acting non-benzodiazepine hypnotics like zolpidem (5 mg) have been studied at 3,500 meters. One 2017 trial found it only reduced oxygen saturation by 2.3% compared to placebo-much less than traditional sedatives. The CDC Yellow Book 2024 says zolpidem can be used cautiously, as long as you wait at least 8 hours after taking it before doing anything physical. That means no hiking, climbing, or skiing the next morning.

Melatonin (0.5-5 mg) is another option. It doesn’t suppress breathing. Small studies suggest it may even help stabilize sleep without affecting oxygen levels. The CDC doesn’t have enough data to officially recommend it for altitude, but it’s not flagged as dangerous either. Many travelers report better sleep with melatonin and no side effects.

But here’s what you shouldn’t use:

- Alcohol-reduces breathing response by 25%

- Benzodiazepines (diazepam, lorazepam, alprazolam)-cut ventilation by 15-30%

- Opioids (codeine, oxycodone, morphine)-can drop SpO2 below 80%

- Barbiturates and other strong sedatives-avoid entirely

What Experts Say-And Why You Should Listen

The consensus among top altitude medicine specialists is unanimous. Dr. Peter Hackett, director of the Institute for Altitude Medicine, says: "Any medication that depresses respiration is contraindicated above 2,500 meters." Dr. Andrew Luks, co-author of the Wilderness Medical Society’s guidelines, warns that sedatives can worsen periodic breathing and trigger full-blown altitude sickness. Dr. Paul Auerbach, editor of Auerbach’s Wilderness Medicine, is even clearer: "Benzodiazepines may worsen hypoxemia and should be avoided." The CDC Yellow Book 2024 doesn’t mince words: "Respiratory depressants such as alcohol and opiates should be avoided at high altitude." Healthdirect Australia and the Cleveland Clinic echo the same warning. This isn’t just opinion-it’s based on decades of physiological research and real-world outcomes.

Real People, Real Consequences

Online forums are full of stories that match the science. On Reddit’s r/climbing, one user took a single 5 mg zolpidem at 4,000 meters and saw their SpO2 drop to 79%. Another reported severe nausea after two beers at 3,500 meters-symptoms that cleared only after descending. A survey of 1,247 trekkers found that 68% who drank alcohol during acclimatization had worse altitude sickness than those who didn’t.

These aren’t just anecdotes. They’re warning signs. When your body is already fighting to get enough oxygen, adding a sedative is like removing one of your lungs.

What to Do Instead

You don’t need sedatives to sleep well at altitude. Here’s what actually works:

- Ascend slowly. Give yourself 24-48 hours to adjust before going above 2,500 meters.

- Avoid alcohol for the first 48 hours. Even one drink can undo your body’s adaptation.

- Use acetazolamide (125 mg twice daily). This prescription medication helps your body adapt faster and improves oxygen levels during sleep.

- Try melatonin (1-3 mg) at bedtime. It’s safe, natural, and doesn’t suppress breathing.

- Use a pulse oximeter. Knowing your oxygen saturation in real time helps you catch problems early. Sales of these devices have jumped 22% in the past year-because people are learning the hard way.

Professional mountain guides follow strict no-sedative policies. IFMGA-certified guides, who lead expeditions in the Himalayas and Andes, have a 89% compliance rate with this rule. If they can’t use sedatives on a 6,000-meter climb, you shouldn’t either.

The Bottom Line

High-altitude travel is thrilling. But it’s not a vacation you can treat like a weekend getaway. Your body is under stress. Every decision matters. Sedatives might seem like a quick fix for sleep, but they’re a gamble with your oxygen. And when oxygen drops, your brain, heart, and lungs pay the price.

There’s no shortcut to acclimatization. Slow ascent, hydration, and avoiding respiratory depressants are the only proven ways to stay safe. If you need help sleeping, talk to a travel medicine specialist at least 4-6 weeks before your trip. Don’t wait until you’re at 4,000 meters to realize you made a mistake.

Can I take melatonin at high altitude?

Yes, melatonin (0.5-5 mg) is generally considered safe at high altitude. Unlike benzodiazepines or alcohol, it does not suppress breathing or reduce your body’s natural response to low oxygen. Small studies suggest it may even improve sleep quality without worsening oxygen levels. However, the CDC notes it hasn’t been formally studied for altitude-specific sleep issues, so use it cautiously and avoid high doses.

Is zolpidem safe for sleep at high altitude?

Zolpidem (5 mg) is one of the few sedatives the CDC considers potentially safe at altitude, based on recent studies. It causes only a minor drop in oxygen saturation-about 2.3%-compared to placebo. But you must wait at least 8 hours after taking it before doing any physical activity. Never take it if you’re planning to climb, hike, or drive the next day. Even then, use it only if other options fail and under medical supervision.

Why is alcohol dangerous at high altitude?

Alcohol reduces your body’s ability to respond to low oxygen by about 25%, even at low doses. It also dehydrates you and worsens the periodic breathing cycle common at altitude. Studies show people who drink alcohol during acclimatization are nearly twice as likely to develop severe altitude sickness. A single beer can drop your nighttime oxygen saturation by 5-10 percentage points, putting you at risk for confusion, nausea, and even fluid buildup in the lungs or brain.

What are the signs that a sedative is affecting my breathing at altitude?

Watch for worsening symptoms after taking a sedative: increased headache, nausea, dizziness, extreme fatigue, confusion, or shortness of breath at rest. If your oxygen saturation (measured by a pulse oximeter) drops below 85% while resting, or if you notice long pauses in breathing during sleep, stop the medication immediately and descend. These are signs your body is struggling to compensate.

Can I use sleeping pills if I have a medical condition like insomnia?

If you have chronic insomnia, talk to a travel medicine specialist before your trip. Do not assume your usual medication is safe. Many common sleep aids are respiratory depressants and are dangerous at altitude. Alternatives like melatonin, behavioral sleep strategies, or acetazolamide (which improves sleep quality at altitude) are often better options. Never self-prescribe or rely on online advice when planning a high-altitude trip.

okay but like… i took a melatonin gummy at 4k meters and woke up feeling like a zombie? like, my head felt full of cotton and i couldnt even walk to the bathroom without holding the wall. so uh… maybe it’s not all sunshine and rainbows? 🤔