When a brand-name drug loses its patent, the first generic version hits the market-and prices usually drop by about 13%. That sounds good, right? But here’s the real story: the biggest savings don’t come from the first generic. They come from the second and third ones.

Why the First Generic Isn’t Enough

The first generic manufacturer gets a 180-day exclusivity window under U.S. law. That means they’re the only one allowed to sell the generic version for half a year. During that time, they can charge a premium-sometimes as high as 87% of the original brand price. Patients still pay a lot. Pharmacies still struggle to keep shelves stocked affordably. And insurers? They’re not seeing the savings they expected. That’s because the first generic has no real competition. There’s no pressure to lower prices. No reason to offer discounts. No incentive to cut costs. So the price stays high-even though the drug is no longer patented.The Real Price Drop Starts With the Second Generic

Once the exclusivity period ends and a second company enters the market, everything changes. Prices don’t just dip-they plummet. Data from the FDA shows that when the second generic arrives, the average price falls to about 58% of the original brand price. That’s a 30% drop in just a few months. Why? Because now there’s a choice. Two companies are selling the same pill. One has to undercut the other to win contracts with pharmacies, hospitals, and PBMs (pharmacy benefit managers). It’s simple economics: more sellers = lower prices. This isn’t theoretical. In 2020, a generic version of the blood pressure drug amlodipine was sold by one manufacturer at $0.30 per pill. When a second company entered, the price dropped to $0.15. Within six months, a third manufacturer joined-and the price fell to $0.08. That’s an 73% reduction from the original brand price.Third Generic? That’s When Savings Really Multiply

The third generic doesn’t just add another option-it triggers a chain reaction. With three or more manufacturers competing, prices often fall to 42% of the brand’s original cost. In some cases, they drop even lower. The ASPE (Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation) found that markets with three generic competitors see a 20% further price reduction compared to duopolies. That’s not a small bump-it’s a massive win for patients and payers. And it gets better. In high-volume markets-like metformin for diabetes or atorvastatin for cholesterol-there can be 10 or more generic makers. In those cases, prices often fall to just 5-10% of the brand price. One study found that a 100-count bottle of generic atorvastatin dropped from $120 under the brand to under $3 with 12 manufacturers competing.

What Happens When Competition Fades

Here’s the scary part: if one of those manufacturers exits the market, prices can spike overnight. A 2017 study from the University of Florida looked at 150 generic drugs. Nearly half were being sold by only two companies. When one of those two shut down production-due to low margins, supply issues, or consolidation-the price jumped by 100% to 300% in just a few months. That’s not a glitch. That’s how the system works. Without enough competitors, the remaining manufacturer has no reason to keep prices low. And with only one or two players left, they can quietly raise prices without fear of losing customers. This is why consolidation in the generic industry is so dangerous. When Teva bought Allergan’s generics business, or when Mylan and Upjohn merged into Viatris, the number of independent manufacturers shrank. Fewer players means less competition. Less competition means higher prices.Who’s Really in Control?

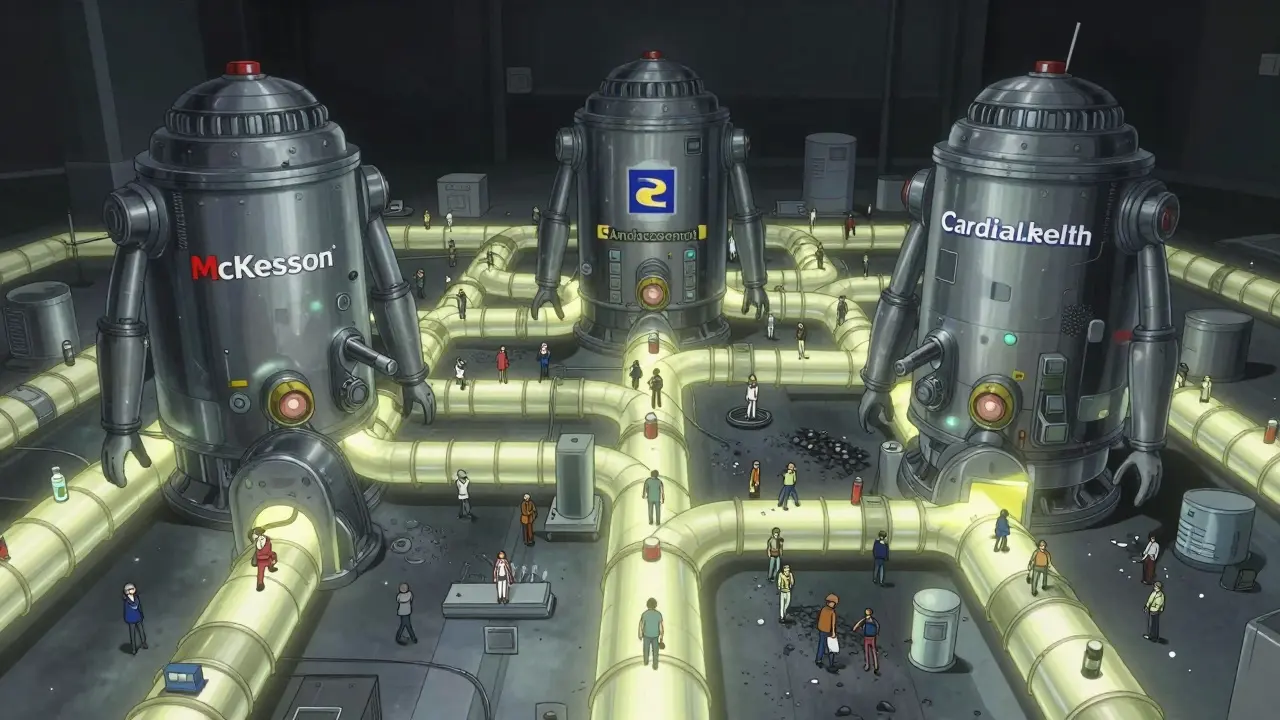

You’d think more generics means more power for patients. But the reality is more complicated. The real power now lies with three giant wholesalers-McKesson, AmerisourceBergen, and Cardinal Health-who control 85% of the generic drug distribution network. And three big PBMs-Express Scripts, CVS Health, and UnitedHealth’s Optum-handle 80% of prescription claims. These middlemen don’t care how many generic makers there are. They care about what discount they can squeeze out of each one. So even if there are five generic versions of a drug, if the PBM only negotiates with the two cheapest ones, the other three get pushed out. And then? Prices start creeping back up. That’s why some markets with dozens of manufacturers still have high prices. It’s not about how many exist-it’s about who gets to sell.Anti-Competitive Tactics That Block Savings

Brand-name drug companies don’t just wait for patents to expire. They fight to keep generics out. One common trick? “Pay for delay.” A brand company pays a generic manufacturer to hold off on launching their version. The FDA estimates this costs patients $3 billion a year in higher out-of-pocket costs alone. Another? “Patent thickets.” A single drug can be protected by dozens of overlapping patents-some covering the pill’s shape, others its coating, others its manufacturing process. In one case, a blockbuster drug had 75 patents, extending its monopoly from 2016 all the way to 2034. These aren’t accidents. They’re strategies. And they work-until regulators step in.

What’s Being Done About It?

There’s some progress. The CREATES Act, passed in 2022, makes it harder for brand companies to block generic manufacturers from getting samples they need to test their drugs. The FDA’s GDUFA III program, running through 2027, is speeding up approvals for complex generics-like inhalers and injectables-that used to take years to enter the market. Bipartisan bills like the Preserve Access to Affordable Generics Act aim to ban “pay for delay” deals outright. If passed, they could save $45 billion over ten years. But the real solution? More competition. Not just one or two generics. Not just the ones that get picked by PBMs. But real, open, unfettered competition from as many manufacturers as possible.What This Means for You

If you’re paying for a generic drug, ask your pharmacist: “How many companies make this version?” If the answer is one or two, it might be worth checking if another version is available. Sometimes, switching to a different generic manufacturer can cut your cost in half. If you’re on Medicare or private insurance, ask your plan if they’re using the lowest-cost generic option. Many plans default to the first one they negotiated with-not the cheapest one on the market. And if you’re a patient advocate, a policymaker, or just someone who cares about affordable medicine-push for policies that encourage more generic entrants. Not just the first. Not just the big ones. All of them. The data is clear: the second and third generics are the real price killers. They’re not just alternatives-they’re the reason millions of Americans can afford their prescriptions at all.What’s Next?

Without sustained pressure to keep the market open, we risk slipping back into the old pattern: high prices, few choices, and surprise spikes when one manufacturer quits. The good news? We know how to fix it. We’ve seen it work. We’ve measured it. We’ve saved billions because of it. Now we just need to make sure it keeps happening.Why do generic drug prices drop so much after the second manufacturer enters?

When a second generic enters the market, the first manufacturer can no longer charge a premium. To keep customers, they must lower their price. This triggers a price war. The second manufacturer lowers their price to compete, and the first responds. This back-and-forth drives prices down quickly. By the time the third manufacturer joins, prices are often cut in half-or more-compared to the brand-name drug.

Do all generic drugs get cheaper with more competitors?

Not always. The biggest price drops happen in high-demand drugs-like those used for diabetes, high blood pressure, or cholesterol-where thousands of prescriptions are filled each month. In low-volume markets, manufacturers may not bother entering, even if the patent expires. That’s why some generics stay expensive: there’s no competition because no one else sees the profit potential.

Can I ask my pharmacy for a cheaper generic version?

Yes. Pharmacists can often switch you to a different generic manufacturer if your insurance allows it. Ask them: “Is there another generic version of this drug that’s less expensive?” Sometimes, the difference is $20 or more per month. It’s worth checking.

Why do some generic drugs suddenly become expensive?

It usually happens when one of the manufacturers stops making the drug-due to low profits, supply issues, or consolidation. If only one or two companies are left, they can raise prices without losing customers. This is common in markets that started with three or more generics but lost competitors over time.

How do pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) affect generic drug prices?

PBMs negotiate discounts with manufacturers, but they often favor only one or two generics-even if more are available. This reduces competition and can keep prices higher than they should be. They’re paid based on rebates, not on how low the final price is, which creates a misaligned incentive.

Is there a way to know how many companies make my generic drug?

Yes. Look at the drug’s label-the manufacturer’s name is printed on the bottle. You can also search the drug name + “generic manufacturers” online. The FDA’s Drugs@FDA database lists all approved versions. If you see only one or two names, competition is limited.

What’s the impact of generic drug competition on Medicare?

Medicare saved over $265 billion from 2018 to 2020 thanks to generic competition, according to the FDA. Each additional generic manufacturer reduces the program’s spending. Without second and third generics, Medicare spending on prescriptions would be billions higher each year.

This is why I always ask my pharmacist for the cheapest generic-even if it’s not the one my doctor picked. Last month I switched my blood pressure med from the first generic to a third-party version and saved $45 a month. That’s a pizza night every week. Why settle for less when the system literally rewards you for digging a little deeper?

Also, check the label. The manufacturer’s name is right there. If you see only one or two names, you’re being played. There are always more options.